Prospect Cottage – the distinctively black and yellow former home of pioneering filmmaker, artist and gardener Derek Jarman – has long been a site of pilgrimage for fans of his filmmaking, his art and his garden. This weekend (2-3 December), among its usual objects, are two strings of painted scenes for a film-adaption of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, stretched across the cottage’s conservatory.

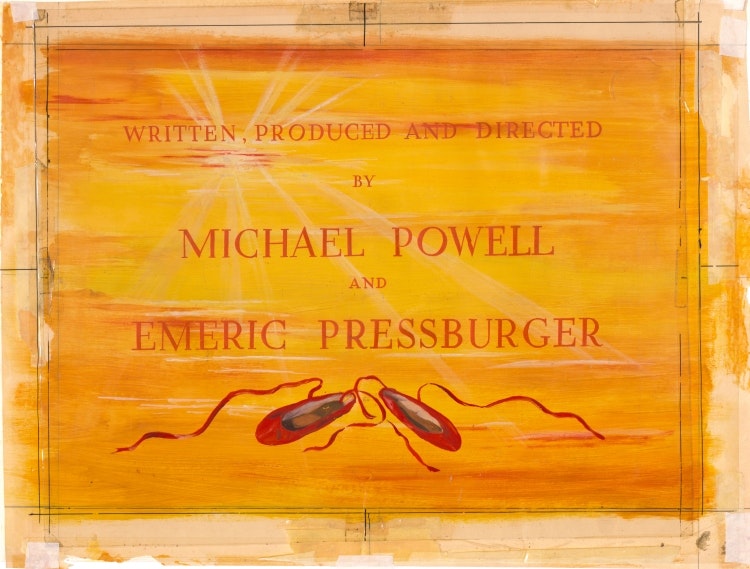

But while Jarman realised his film of The Tempest in 1979, these designs are not for his production, but for an unrealised one by British film director Michael Powell. Best known for his work with Emeric Pressburger, the pair brought radical filmmaking and Technicolor fantasy to the British film industry during the Second World War and post-war era through a filmography that includes A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948).

Jarman was of a later generation, and had a different, more abstract approach to cinema, but his own radical sensibility owes a huge amount to Powell & Pressburger’s films.

To explore this relationship, Powell and Jarman have been brought together in the richly layered space of Prospect Cottage for the exhibition, Powell + Pressburger: In Prospero’s room, curated by British Film Institute (BFI) cultural programme manager Rhidian Davis, working with arts charity Creative Folkestone, the current custodians of the cottage.

It makes up part of the BFI’s current season, Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger, which looks not only to explore the directors’ work but also that of their collaborators from set designers to cinematographers – as well as those who came after, such as Jarman.

In the intimate space of Prospect Cottage, the set designs by Powell collaborator Ivor Beddoes sit alongside a large plaster head of a classical sculpture used in Jarman’s own Tempest, creating a dialogue between the two directors.

Davis explains that there was already much shared influence between the two, not least their links to the Kent landscape. Having grown up in Bekesbourne, near Canterbury himself, Powell used the landscape of his childhood for his evocative 1944 film A Canterbury Tale, for instance, while in his later years Jarman drew inspiration from Dungeness’ wilderness.

Jarman “became very interested in Michael Powell’s work” in the 1970s, according to Davis. A 1978 retrospective of his work at the National Film Theatre in London (now the BFI) “particularly fired [Jarman’s] imagination” in the period in which he was making The Tempest, he says.

Juxtaposing the designs for Powell’s ‘Magic Island’ – the title for his Tempest adaptation that never was – with Jarman’s assortment of alchemical books and objects such as two crystal balls reported to have belonged to English occultist Aleister Crowley shows the importance of the figure of the Magus, or “magician as creator”, says Davis, exemplified in the context of The Tempest by its protagonist Prospero.

While Jarman did not draw too closely to Powell’s own vision, their shared interest was evident. Jarman has expressed feeling indebted in some way: “I’ve never met Michael Powell, but when I was making The Tempest, I knew that he had long wanted to film the play,” Jarman told film historian and critic Ian Christie. “I kept saying to my producer, ‘Michael Powell should be making this – I’ve stolen it from him’”.

“The wider stories of the Archers”

Davis explains that the BFI season not only looks to celebrate the filmmakers, but to also “get the wider stories of the Archers family out there” – referring to the production company founded by the filmmakers, which comprised talented collaborators from Ivor Beddoes and Hein Heckroth on production and costume design, to cinematographer Jack Cardiff.

Their design legacy is awarded recognition in a current exhibition at BFI Southbank, The Red Shoes: Beyond the mirror, open until 7 January. Curated by Claire Smith and Sue Prichard and designed by Simon Costin, the exhibition brings together material from the BFI National Archive’s collections, looking to “pull back the curtain on what makes The Red Shoes such a defining piece of filmmaking”, says Smith.

Meanwhile a new book, The Cinema of Powell & Pressburger, speaks to influential designers, artists and actors working today – from Barbie production designer Sarah Greenwood to costume designer Sandy Powell – who each write about the profound influence the filmmakers had on their own work.

While Powell never made his Tempest, nor many other projects as the filmmakers’ fantastic style was eclipsed by a taste for British social realism, theirs and the Archers’ legacy can be traced through many celebrated creatives that came after.

Powell + Pressburger: In Prospero’s Room is at Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, on 2 and 3 December 2023

Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger runs until 31 December at various sites across the UK and online through the BFI Player.

- Design disciplines in this article

- Industries in this article

- Brands in this article