“With the current lack of physical exhibitions and social gatherings, where you’d usually find opportunities, we need to rethink our methods of community building and artist career development,” says Ema Marinova.

Marinova is the founder of Cluster, a London-based art fair. Like most events-based companies, the pandemic has up-ended Cluster’s business and left the team wondering how it can continue to engage artists and designers during the biggest threat to the creative industry in a generation.

In response to these thoughts, later this year the Cluster studio will welcome its first ever illustrator in residence. As Marinova tells Design Week: “We had to come up with an initiative that keeps supporting individuals in the arts.”

What is a residency?

Residency programmes vary from institutions to institution – but most follow the common thread of supporting early-career creatives to evolve and strengthen their practice. Some programmes can be targeted at specific disciplines, like games design, fashion or illustration, while others are open to all forms of creativity.

Over at Cluster, Marinova says their residency will be tailored to the chosen illustrator.

“Once the artist is selected, we will tailor a mentorship programme specific to their and the project’s needs,” she says. “That means we will bring industry professionals to the resident’s doorstep and look closely at how they can contribute to the process.”

On top of career support, lifestyle funding can also be part of the residency experience. Cluster’s residency will cover the cost of the recipient’s transport, food, flights, materials and accommodation, according to Marinova.

What do you need to apply for a residency?

The answer to most of these questions is: it depends. In the case of what you might need to apply for a residency, it depends on the type of programme you’re applying for.

Some residency programmes ask you to have an idea of the kind of project you’re looking to work on during your time there. Others are less prescriptive. In any case, it’s good to be flexible with your intentions and not be fixed to one way of doing things.

Matteo Menapace was games designer in residence at the V&A in 2019. He tells Design Week that while he entered his residency promising to do “probably more than I could handle”, he soon realised he didn’t need to prioritise quantity to make the most of the experience.

“I eventually found out that it was okay to not go into the experience with a specific outcome in mind – the plan is always meant to change,” Menapace says. He explains the support around him allowed him to question, evaluate and progress his ideas beyond his original plans.

What will I actually do during a residency?

The beauty of the residency programme is that what you spend your time doing is largely down to you – you’re able to follow your interests down various paths in order to develop your overarching idea or practice. That said, certain institutions will have different expectations of how you might move through their programmes.

Menapace explains that while working with the V&A he and his fellow design residents were involved in a lot of “outward-facing” work with the museum’s Learning Department.

“We were doing two open studios a month, which meant around a quarter of our time was centred on this,” he says. “We also spent a lot of time doing workshops with school groups and teachers – and then of course we had time to focus on our own projects.”

During the nine-month V&A residency Menapace, who specialises in user experience design and games, created and prototyped two games.

Other residencies, like the Design Museum’s Designers in Residence, have their teams working towards an exhibition which addresses a broader theme at the end of the experience. Abiola Onabule, who was part of the programme’s 2020 cohort, says this shared end goal gives way to plenty of collaboration.

“It’s all been conducted over the internet, via zoom and teams and we’ve only met a couple of times in person,” she says, explaining the effect the pandemic has had on the experience. “The majority of the work has been done separately, in our respective homes, and yet we’ve been in contact so much and it’s felt so collaborative and communal. It’s a very different experience than I could have imagined, but it’s been so interesting.”

How could it influence my long-term career?

Onabule tells Design Week her experience as a resident acted as a sort of “ideas incubator”.

As a designer working in fashion, she explains her industry is fast-moving, so having the time to collaborate with designers from very different practices has allowed her to “really research, learn, talk with people and explore ideas and concepts”.

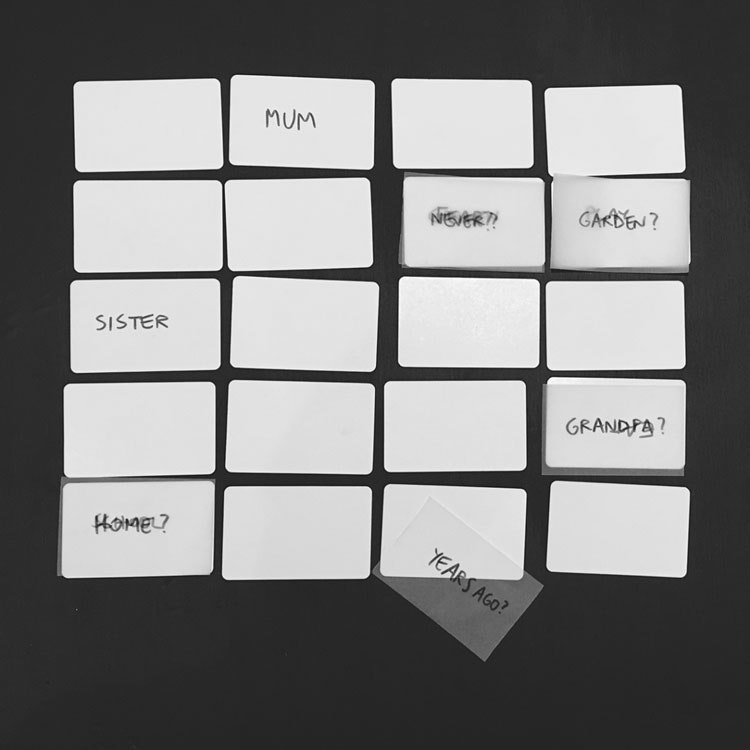

Her work at the Design Museum investigated how the exchange of craft and skills could be an act of care. It explored the stories of West African women living in the UK. She says the work she did here helped her unearth topics she intends to continue with “far into the future”.

Meanwhile Menapace explains that even nearly two years on, the work he is doing now is still influenced by what he learned during his time at the V&A.

“Before I started with the V&A I was still making games but as a hobby essentially – this helped me completely convert my practice,” he says.

And Marinova, who sits on the other side of the experience as the facilitator, says a good residency should provide close mentorship so as to help designers “flourish” in their later careers.

Is a residency better than further education or masters study?

Competition is tight with residencies and it goes without saying that there are not that many of them. However there are some considerable benefits to residency programmes that university courses often can’t match up to. Financial support, one-to-one mentorship and the ability to bring your idea before an audience are just some of what’s on offer. Additionally, for those with more niche interests, residencies have the power to put you in contact with like-minded individuals.

“One of the factors that made my residency so helpful was the constant feedback with people in the V&A Learning Department,” says Menapace. “It was almost like being back at college, but with less of a hierarchy – instead of being student and teacher I would speak with my supervisors peer to peer.”

Having done both a masters and a residency, Onabule says residencies give you the “freedom and time as a creative to explore what you want your work to say and stand for”. Where a degree aims to equip many people with a broad understanding of a topic, she says her experience of the Design Museum’s residency programme is more focused.

“It is a tailored program, where you are the focus of the process,” says Onabule.

Are there any negatives?

The glaring problem with residency programmes is their scarcity. While more pop each year – including the upcoming Cluster programme which is still taking applications – they remain in short supply.

Marinova hopes this will change in the future.

“I strongly believe alternative experiences can be key to personal discovery, pushing your own creative boundaries and reaching significant results,” she says. “In these current times, the creative industry should be definitely looking to explore alternative ways of how it can support early-career artists.”

Where can I find out more information?

Cluster (open to applications until 20 January).

The Design Museum.

The V&A.

The British Council.

- Design disciplines in this article

- Industries in this article

- Brands in this article