The frontline of the fight against a global pandemic isn’t necessarily where you’d expect to find teams of dedicated games designers. But as the coronavirus crisis proves, video games can be a crucial tool in helping doctors and the general public deal with public health matters.

The relationship between video games and medicine is a developing one. Medically accurate simulations and games have grown in popularity in recent years – last year, Design Week covered the work of US-based games developer Level Ex, whose smartphone games are helping doctors maintain their surgical and diagnostic skills – but the practice rarely gets spoken about outside of medical circles.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, however, games designers have the opportunity to showcase the utility of their craft on a very public stage.

“Games are excellent tools for engagement”

Back in June, Glasgow-based design studio Game Doctor was awarded a £50,000 grant by Innovate UK to develop a “casual mobile game” to educate young people about the coronavirus.

“[Casual games] are simple games which can be played and mastered quickly, and are accessible to a widespread audience,” Game Doctor founder and science director Carla Brown tells Design Week. The nature of these games, usually played via a users’ smartphone, make them excellent conduits for information, she adds.

Brown set up Game Doctor in 2016, having developed educational games during her PhD and in several museum and academic roles. This experience saw her design games for complex health topics like HIV and bowel disease, as well as manage an “international online gamified resource for young people on hygiene and infections” for Public Health England.

“Through this work I witnessed the real-time benefits of using games for health education – games allow you to visualise and interact with very complex and ‘invisible’ concepts, and allow you to tell emotive stories through characters and environments,” Brown says.

“Balancing educational with engaging is always a challenge”

The coronavirus education game that the studio is working on right now is being developed in collaboration with health psychologists from the University of Stirling and COVID-19 researchers at the University of Glasgow and Queens University Belfast. It will be soft launched in schools in UK schools in September.

“The core mechanics of the game involves players developing unique strategies against COVID-19 involving the immune system and drugs,” Brown says. “Through the game, the player also researches and develops a vaccine against the virus.”

As we already know, it is designed to be a casual game and thus simple and accessible. But as Brown explains, designing something simple and accessible, especially in the context of cutting-edge science and virology, isn’t necessarily so straightforward.

“We’re often working with really complex science that has to be accurate,” she says. “And balancing educational with engaging is always a challenge – on paper a mechanic looks really exciting and engaging but then when you get it in the game it can be boring or confusing.”

“Games need not be complex to change clinical procedures for the better”

Coronavirus is just the latest area in health and medicine for the team to focus on – previous projects have tackled everything from epigenetics, to vaccination and sexually transmitted infections. The range of topics reflects the growing demand for gamified learning.

And beyond just learning through casual play, games are increasingly finding their way into clinical settings, according to practicing medical doctor, medical illustrator and creative director Dr Ciléin Kearns.

“Medics often find the more experienced they become, the more they struggle to explain problems or solutions to patients and trainees without using complex medical language or walls of text,” he says. Games can be a way around this, Kearns explains, having written on this topic in its infancy for the Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine in 2016.

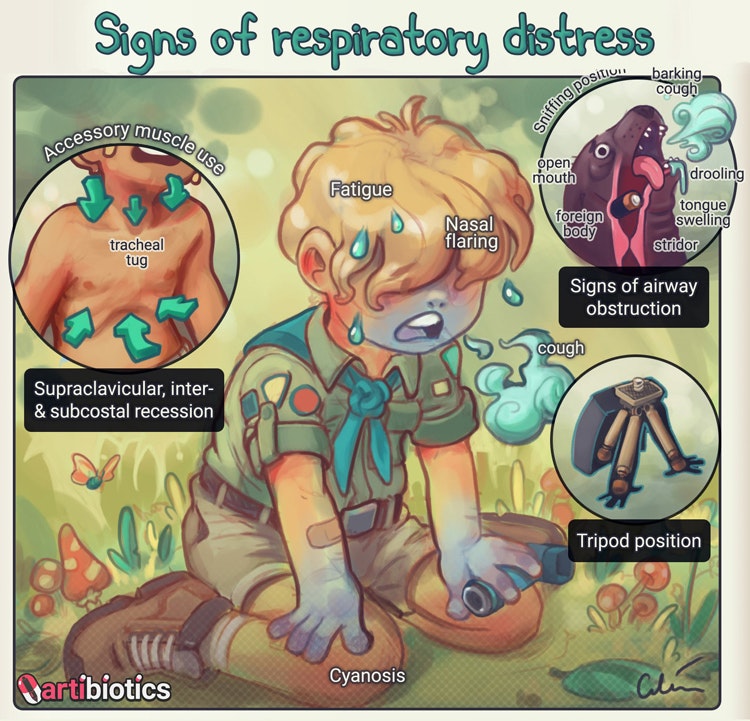

Kearns gives the example of a breathing test game, designed by a New Zealand-based team, that is now being used in respiratory research, which helps medical professionals measure the level of inflammation in the lungs. The game features a “cute cloud”, he says, which patients control and push to a finish line through their rate of breathing out.

“This simple game makes the procedure easy to understand by giving the patient real-time visual feedback, ensuring consistent and comparable measures are taken,” he says, adding that “games need not be complex to change clinical practice for the better”.

“The number one priority is collaboration”

Echoing Brown’s work, Kearns stresses the role of the science in medical gaming.

“Without a doubt the number one priority is collaboration between experts in video games and the health condition of interest,” he says. Experts for the latter can include patients, as well as healthcare professionals, he adds.

And as with any video game, user experience must be a main focus too – design choices, Kearns explains, should serve the intended message of the game.

“Two helpful guiding principles in medical illustration are to remove unnecessary detail and accentuate the important information,” he says. In a gaming context, these look like relatively simple interactions, with clinically effective information embedded throughout.

“How people feel is often overlooked”

As Kearns points out, the nature of video gaming gives way to endless possibilities as to the format of medical games – there is “no one-size-fits-all”, he says. The aforementioned cloud breathing game and Game Doctor’s smartphone and web-based games are but a sample of what creatives are doing in the field right now.

But one example that deviates entirely from these is InsideOut, an “ingestible game” from the designers and researchers at the Exertion Games Lab based out of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

As its “ingestible” description might suggest, InsideOut is a gamified experience for patients undergoing a capsule endoscopy – that is, where a tiny wireless camera with a sensor is swallowed so that doctors can capture footage of a patient’s digestive tract. The procedure is common, but understandably causes considerable anxiety for some and this is the motivation for the game.

“Current research around imaging capsules mostly focuses on the technical side or the functional perspective, while the experiential perspective – how people feel – is often overlooked,” says game designer, PhD candidate and InsideOut researcher Zhuying Li.

“As human-computer interaction researchers, we know the importance of the experiential perspective for a certain technology and therefore are interested in exploring the experiential perspective of the imaging capsule through game design thinking,” she adds.

A more “humanised technology future”

An endoscopy procedure already requires patients to swallow a capsule: what Li and team have created to supplement this is a wearable device that shows video captured by the capsule for the patient to see. The software found on the screens, worn around the waist, maps the patient’s body movements using various video game-like manipulations, such as “scaling, rotation, balancing and speed”.

“The combination of imaging capsule and play can benefit various stakeholders,” Li tells Design Week. “If used in a clinical setting, the combination can make the capsule endoscopy procedure more fun and let patients engage with their own bodily data.”

The consequence of this, Li says, is a more “humanised technology future” in a medical context: “[We’re aiming to] emphasise the human when it comes to the design of future technology interactions”.

“Walk in another’s shoes”

It is clear from speaking to Li, Brown and Kearns that the relationship between gaming and medicine is flourishing. Games like InsideOut, Li says, can be a catalyst for other designers to get involved with and rethink medical experiences.

This potential for good is something that Kearns also recognises. He suggests some of the most inherent traits of gaming could completely retrace how medicine is thought about.

“The ability to ‘walk in another’s shoes’ is one of the most unique features of the video game medium and has the potential to help address health inequities by creating wide awareness and empathy,” says Kearns.

“I would love to see this used more in games to explore authentic perspectives from the diversity of the human experience, from culture to ability.”

- Design disciplines in this article

- Industries in this article

- Brands in this article

One response to “Designing better public health awareness through video games”

There’s an exciting future ahead!