Unicef has launched a mobile game to teach children in Latin America and the Caribbean about their rights.

Right Runner has been designed by London-based design studio, Nexus (which also has offices in Los Angeles). Deborah Casswell, the studio’s creative director, says that the studio worked with UNICEF to work out an “engaging” way to educate children about their rights.

As 2019 marks 30 years since the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the game seeks to address children who are unaware of the rights enshrined in this agreement.

While Unicef chose to focus on five core rights for this game, Casswell says that that it is in talks for expansion.

“A new way of engaging with young people”

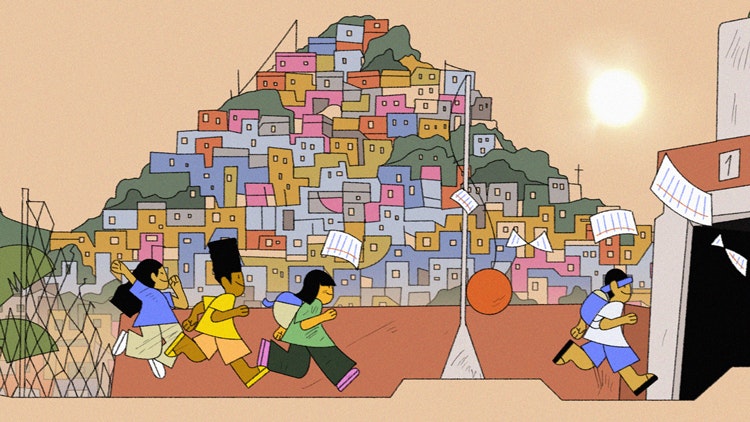

The game is in an endless runner format, with five levels covering five rights, and players try to climb to the top of a mountain. The runner format was chosen because it was “instantly familiar”, Casswell says. “There are as few entry barriers as possible,” she adds.

For the design team, the app format offered a platform to explore customisation.

“With a runner there’s a lot of opportunity to use soft messaging in the environments,” Casswell says. “And if you can create a familiar environment, we are much more likely to engage and relate to it.”

Five levels cover five human rights: the right to play, the right to learn, the right to live in a clean and safe environment, the right to live a life free from violence and the right to be heard.

The worlds of the game are inspired by the countries targeted; the favelas in Brazil are the backdrop for the right to learn while the right to be heard level takes place on a mountain top in the Andes.

If a player doesn’t complete a task, they don’t go back to beginning but start from where they were. There are tailored details for the subject matter; levels are rated for completion based on factors like rights claimed, and friends found — highlighting the collective power of young people was a focus for the game, according to Caswell.

“Relatable” details

Unicef’s youth ambassadors were consulted during the development of the game, on details ranging from how areas should look, to the style of music, down to the type of backpack a young person in a favela might have.

By focusing on what was recognisable to young people in Latin America and the Caribbean, Caswell says the team could create situations and characters that were “really relatable”.

This was also achieved through character design, by creating players that looked like young people in Latin America and the Caribbean.

“We made sure to represent all the different kinds of people in the region so that it reflected the community we were talking to,” Caswell says.

Caswell says: “Some rights might sound obvious from our point of view but in the region that we’re talking to, a lot of young people don’t even know they have those rights — that they should go to school. If their parents or their community don’t prioritise that, and it’s not a cultural norm, they don’t know to fight for it yet.

“Making it clear that these are things you deserve is a massive first step.”

Striking a balance between “realistic” and “fun”

The team worked to recreate situations that were “realistic”, as set out by Unicef and its youth ambassadors.

But it was a challenge to “make sure it was a game that was fun but at the same time representative of the very real obstacles that the players are experiencing in real life.”

This was partly achieved through a staggering of concepts over levels. The first level, for example, explores the right to play, which is an “easier entry-point” than the right to be protected from sexual and physical violence, which is explored in level four.

And how do you balance those more serious concepts within a gaming format? It required a constant looking at the “bigger picture”, Caswell says.

On level four, the studio took a more “metaphorical” approach. The threats were presented through sound, as well as visual metaphors such as hands and chains.

“It’s clear that it’s a threatening environment which is realistic for the young people, but it doesn’t try to depict the actual acts of violence because it’s so different for every victim,” Caswell says.

The game’s illustrative style also allows for this “metaphorical” flexibility.

“Using tone as much as possible” in this way was crucial, as was tailoring the levels to the situations they were based on. The right to learn is a problem for girls in the region, so the studio used a pram with a screaming baby which gets in the player’s way. “The sound alone is blood curdling,” Caswell says.

Right to play?

Although the gaming format is effective, there is a tension involved in Right Runner. If children are not sure about their right to play, will they have any access to a gaming app or a mobile to play it on? According to Caswell, Unicef says that the issues explored in the game affect every social class in the region.

It’s also been formatted for a wide variety of devices and is available in Spanish and English. While it’s available on the Apple Store and Google Home, it can also be played on the Unicef website without the need to download it.

Nexus is not profiting financially from the game in any way; the cost to Unicef covers production hours only.

- Design disciplines in this article

- Industries in this article

- Brands in this article