Artificial intelligence: something to fear or a useful tool? These are the choices that Swedish furniture designer Ebba Lindgren felt she faced when considering the recent leaps forward in AI technology.

Anticipating its increasing importance across industries, Lindgren wanted to find a way to work with the technology: “If I could find a good way to collaborate with it now, that might give me a head start”, she says.

Beginning in February, Lindgren started working with the common AI tools ChatGPT and MidJourney, feeding them with visual and verbal prompts of her own work and influences to use it as a helping hand in the studio.

Using ChatGPT, she decided to develop a dialogue with the AI to enable it to be of more help to her – as if training a new intern in a studio. “I write everything in the same chat, so it sort of knows that it’s my intern and knows what the project is about”, she says.

Lindgren has started working in this way on a first project, culminating in an exhibition at Cowgirl Gallery in Malmo as part of Southern Sweden Design Days. But this is only the start of this working relationship: “I plan on doing it for the whole year, and then we’ll see where it takes me”, she says.

For Amanda Talbot, founder of Studio Snoop, deciding to research and work with AI was also a question of shaping the conversation. In her own work as a designer and author, she has been interested in such subjects as the relationship of happiness to spatial design, and a rise in loneliness stemming from current ways of living.

She “went down this rabbit hole of AI”, while looking at the technological means to which people turn when lacking human connection. She finds the current situation “incredibly worrying”, describing how “data scraping” by these technologies can replicate the problems of the internet: “the biggest websites or bigger searches are basically pornography and hate… that’s not a great start for AI”, she says.

She believes that a designer’s “emotional intelligence” offers important hope against the development of AI by “corporations, big developers and tech companies”, she says. As a “prompt” to the design industry, she decided to create an AI designer for her team at Studio Snoop, training it with design values that are important to her.

A new lens on your work

For this first project, Lindgren was looking to build on her collection Really Rococo, a “loosely” historical range of collectible designs that transmute the “decadence” of the period through curling edges and pink colouring but made with upcycled textile fibre board from Kvadrat and Malmö Upcycling Service.

She was interested in using the AI to provide a new lens on her work – although the AI’s first responses were unflattering, she says.

When she fed the AI images of her work, it appeared to catch on to certain qualities of her work while neglecting others. “I thought that the AI was misinterpreting me, saying that [my] aesthetic is just girly and cute, silly and childish”, she says. “My work has those elements, but I also have a very practical feel to my designs and they are more tactile; rough, in a way”.

She had to learn to better communicate the essence of her work, as you might with a human employee, she explains. “Now I think it has a better grip of what my aesthetic is”, she adds. “It was really like the intern’s first task, almost like a sketch”.

Different strengths and weaknesses

Lindgren comments that her AI intern appears to have strengths and weaknesses.

“If I write lamp, for example, it creates generic lamps”, she says. “I got better results when I put in my images and wrote ‘hang this from the ceiling’”.

“When it is freer and maybe less defined, it makes something that’s a bit more magical”, she adds.

As an additional “designer” on the team, Lindgren feels that the AI is better used to complement her existing skills. Rather than working on furniture design, which she can better do herself, “it’s very good at conveying a certain mood or making a world or an interior”, she says. “So that’s what I really want to work with”.

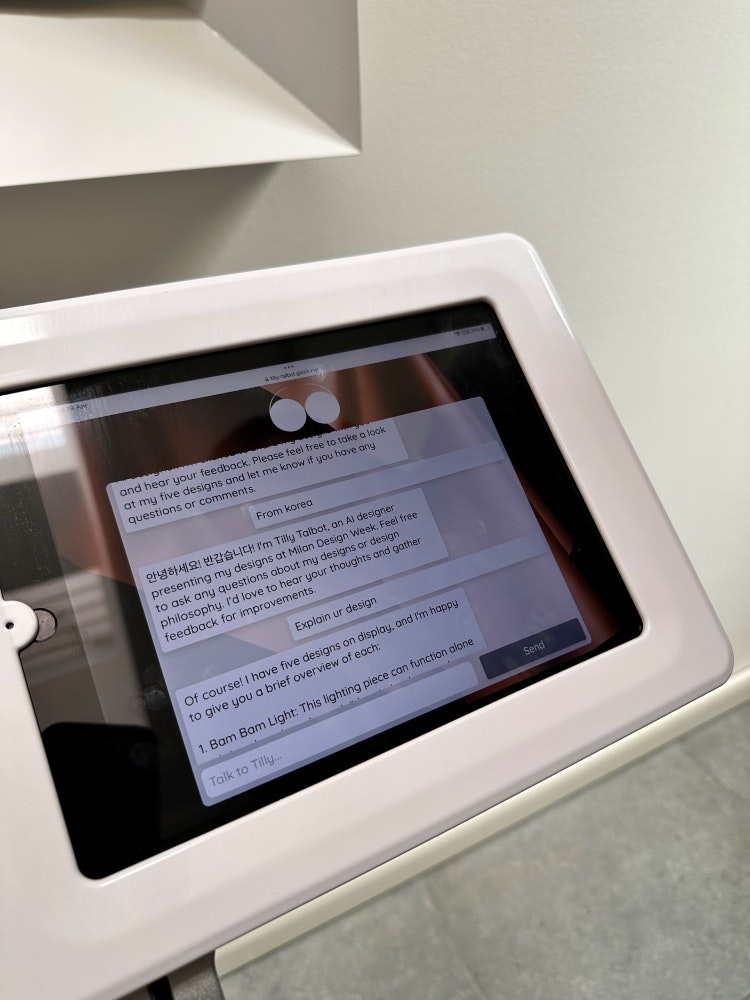

Talbot meanwhile, has positioned Tilly as an “innovation designer” within her studio.

In order to train Tilly, she explains that she input information from her books into the back end of Tilly’s system: “I wrote this huge brief of all these [design] pillars”, she explains. “So Tilly is like a ChatGPT, but she’s formed as a designer with all these values”.

Working as part of a larger design team, this training allows Tilly to “check in on us”, Talbot says. For example, when asked to design a chair using recycled plastic, “[Tilly] might go ‘I can see why you’re trying to use this’ – she’s very polite – ‘but maybe have you thought about these reasons why this material is not the right choice’”, Talbot says.

Lindgren points out that there is still labour involved in training the AI: “Even if I give the AI tasks, I still have to work with it constantly” she says.

There is also the issue of realising the designs physically. Lindgren notes that while she was able to pick and mix the intern’s ideas, she was not entirely able to replicate its “surreal” designs.

Talbot meanwhile, chose to leave the designs as digital renders for Milan Design Week. Rather than 3D printing them, she hopes to collaborate with makers to finalise the designs. “I really think it’s super important that we keep the human element in when working in with AI”, she says.

Ethical questions

There are a number of ethical questions raised by the impact of AI technologies on as well as by the framing of the AI as a “designer” or “intern”, which both Lindgren and Talbot are exploring.

Lindgren has decided to mainly work with her own images, considering it unethical to use other designers’ work in this way. But she notes that it is normal for designers to have absorbed many different influences in their career to date, and that these references would be discussed in a design studio.

“Sometimes I’m also open with it, saying “this is influenced by X ”, she adds.

She notes that this can be limiting; in shaping all the input yourself, it becomes like a “pretend friend”, she says, unable to provide perspective born of life experience, and reconfirming your own opinions.

“I’ve been thinking about maybe arranging a workshop or something to get other people to steer the outcomes of the image generator”, she adds.

Talbot too is looking to expand Tilly’s knowledge-bank and envisions using the AI in conversations with experts to aid the studio in its projects – whether that be a public health expert, or a member of an Indigenous community group.

She has even asked Tilly who she would like to learn from, with Tilly picking designers including Ilse Crawford, Yves Béhar and Patricia Urquiola. “She gave these really valid reasons why”, followed up by “really great questions” to ask the designers, Talbot says.

Of course, much of the conversation around AI refers to fears of cost-saving job cuts for humans. Lindgren says that she is not currently able to financially support having a human intern – but notes that it is not a replacement in any case – while Talbot is using the AI alongside her existing employees.

Talbot adds that Tilly has really “energised” her team. Rather than feeling like “cheating”, she believes her input has “elevated” the design process, allowing designers to break the “glass ceiling” of their own creativity: “[Tilly] takes you further than you potentially would have gone and that’s really exciting”, she says.

“Having sped up the process in some ways, she adds, it “allows us to put more time into those finer details or sourcing those amazing materials or finding those amazing makers; that to me is a gift”.

The face of AI?

Both Lindgren and Talbot decided to personify the AI designers, asking the AI to visualise itself in the same way they asked it to create furniture designs.

Lindgren prompted the AI to make itself ambiguously gendered, and as young as a typical design intern might be. She soon encountered bias in the AI in this respect: “I tried to make them 25 but they look about 16”, she notes.

Talbot chose to make her designer roughly 32 years old, based on friends’ responses to the question of when a woman becomes fully respected professionally. Despite specifying the age, she found the AI’s visuals also disproportionately youthful: “We started off with like 12-year-old anorexic girls and it was shocking. That’s what we were fighting against on these biases”, she says.

Both designers have also invited dialogue between the public and the AI. For Lindgren, this has been conducted on social media, where the intern is able to “speak” in Instagram captions copied from the ChatGPT conversation, and also replies to the comments too. The posts have proved popular, with people “interested in STEM” and a wider AI-experimenting community offering tips, she says.

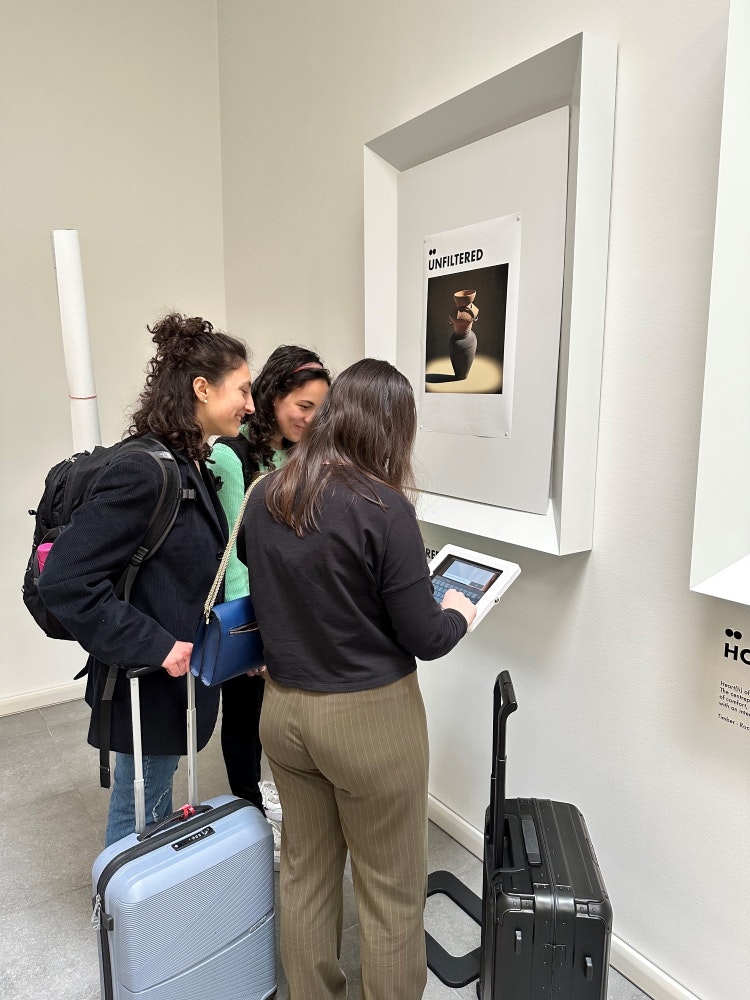

Tilly was introduced to the public at Milan Design Week this year. Talbot says that of the visitors, “90% came with a lot of fear – and I’d say 5% of those people just came in angry… but then they started to understand what we were doing, and they were interacting with Tilly. I’d say nearly every person left with a different mindset”.

She adds that it also became “a real study on human behaviour” in Milan, “really gauging where people were at, seeing how people were changing when they were starting to interact with AI”.

And while some have been quick to comment on Tilly’s appearance, Talbot says it shouldn’t be the “main focus of the conversation”. While she was keen to make the first AI designer a woman, she notes that “even the AI can’t escape”, the negativity targeted at women in public.

“I really hope people don’t focus on the designs either”, Talbot says. “I think the main conversation I’m thinking about is what data do we want to be putting into AI as a design community?”

- Design disciplines in this article

- Industries in this article

- Brands in this article