Continuing with our series of posts from our archives, today we jump forward to 2007, where Yolanda Zappaterra talks to stage designer Es Devlin. Artist and Stage designer, Devlin’s already impressive portfolio has continued to expand since this article was first published 17 years ago.

Kicking off a new operatic season with the world’s most popular production, Georges Bizet’s Carmen, might make you think the English National Opera’s avant-garde reputation has ended. But, in the hands of director Sally Potter and designer Es Devlin, this promises to be the definitive contemporary Carmen, going where no previous interpretation of the gypsy tragedy has gone before.

Devlin has taken the staging and setting to new heights, in keeping with an award-winning body of work that stretches back 11 years to her graduation, first from music, then English literature, then a fine art foundation course at Central St Martins College of Art and Design and finally a stage design course at the non-accredited Motley Theatre Design Course. Since that time, Devlin has blazed a path through theatre and opera design that has taken in productions at the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Royal Court, the Young Vic and through the West End to Broadway, while also producing arresting work in dance for Ballet Rambert, the Northern Ballet Theatre and Cullberg Ballet.

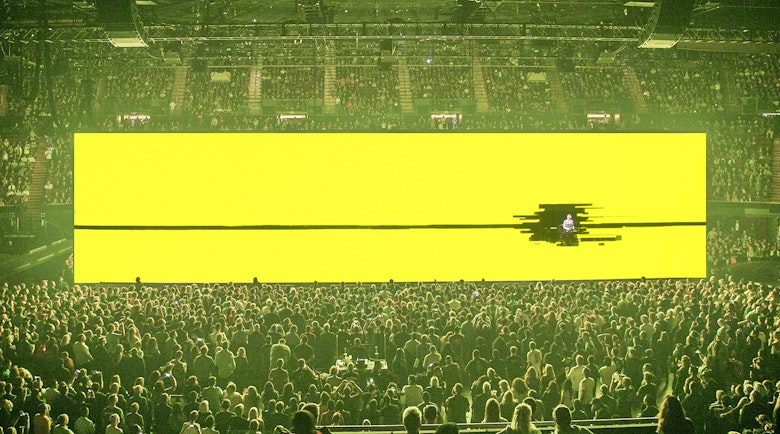

Her designs for live performance and film span the gamut from modest and experimental to monumental. On the small scale, she created the set for the Chapman Brothers and Wire’s performance, Flag Burning, for the Barbican’s Only Connect series in 2003, and was production designer for The Four Dreams of Miss X, directed by Mike Figgis and starring Kate Moss. She also designed Kanye West’s US tour in 2005 and the Pet Shop Boys’ world tour in 2006. Her talents even stretch to converting a Lincolnshire church into an award-winning home for her parents.

What Devlin brings to her work, and the world of live performance, is a determination to do away with the pretend, instead drawing on fine art references, photography, video, literature and the work itself to ‘provide a counterpoint for the drama’. ‘Should a design be engaging so that it is a foil to the action, or should it be a thing that you’d still enjoy even if you walked in on it from Mars, or unable to understand a word? It’s a moot point, but, for better or for worse, I fall into the latter,’ she says.

Part of this approach is rooted in Devlin’s love of art in general, and, in particular, the vibrant Young British Artists scene driving Cool Britannia when she began plying her trade. ‘Just coming out of Central St Martins, I was appalled at the lack of awareness of the current culture of fine art within the theatre,’ she says. ‘The fact that you could still walk into a theatre and view scenery of pretend stuff that looked like pretend stuff, pretend plastic rocks, papier mâché scenery and the like, made it seem like theatre had missed what was going on, and what a vibrant group of artists was achieving.’

‘My response was to refer to [these artists] and to fine art generally,’ she says. And she did, so much so that a colleague later told her ‘that there was a period where my work was whatever had just been at the Tate. There was the Howard Hodgkin moment, the Dan Flavin moment, the Mark Rothko moment’.

At one point Rachel Whiteread’s House served as the starting point for a multi-layered design of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal at the National Theatre, where traces of nine houses were layered to create a startling juxtaposition of 2D imagery and 3D space.

Devlin comes back to this interplay between planes and dimensions repeatedly, and has done so with Carmen, which draws on everything from receding motorway perspectives and Emir Kusturica’s 1988 film The Time of the Gypsies, to the English imagination of Spain and Martin Parr’s book on Benidorm.

The final design is loaded with shapes as metaphors for physical elements. ‘The bullring is there as an arena, but as a perimeter, with action on the outside or inside. Act two is all about crossing lines, so the structure of the café in which the action takes place has a strong vertical line running through it, explains Devlin. ‘The details within each piece are quite naturalistic, but the shapes are quite clearly geometrical. It’s the pure patterns one can perceive while keeping the grit and the dirt of the humanity.’

Would she move to feature films? ‘I find the juxtaposition of scale and the live aspects of my work very thrilling. What a full chorus of voices does to your body, the hairs on the back of your neck rising, that’s what I’m in the game for. Do you get that in movies? Maybe, but I think it’s got to be live. There’ll always be a part of me that wants to push my hand through the cinema screen,’ she says emphatically.

Carmen opens at the London Coliseum on 29 September.

First Published September 2007. Imagery updated in July 2024, courtesy of Es Devlin.

- Design disciplines in this article

- Industries in this article

- Brands in this article