Creative pitching, free pitching, speculative pitching; it comes under many names, but they all involve giving away time and creative ideas for free – or for a very small fee – before you even know you’ve got the job.

The debate around whether this is commercially viable for designers or fair for clients to do is not new, so why is creative pitching still common across the industry?

A lack of protection for designers

Some designers might feel that a paid creative pitch is better than a free pitch when, in fact, “the amount that clients pay almost never covers the amount of time that agencies spend on the pitch”, says Design Business Association head of services Adam Fennelow. There is also the issue that – whether it’s free or paid – designers’ ideas aren’t protected by any intellectual property (IP) laws, Fennelow adds.

This means that, once a designer has given over their ideas, the client could take them and give them to the cheapest agency or their own in-house team. Fennelow suggests that clients often put out paid creative pitches because “then they definitely have the rights to the IP” and it looks less like they’ve “stolen” the idea.

Thinkfarm managing director Stephen Izatt has personal experience of this, as his agency did free creative work as part of a pitch and when the client decided to go with another agency, “they offered to pay around £1000 for the idea” that Thinkfarm had pitched. He says this was “the nail in the coffin” and triggered Thinkfarm’s move away from creative pitching.

Aside from the negatives for designers, Fennelow, Izatt and graphic design studio founder Lucienne Roberts agree that creative pitching isn’t good for the client either.

Most creative pitch documents include some context about the client, technical specifications and a few paragraphs about what the brief is. These can be found within online tender portals, such as Delta eSourcing and Ted Tenders or are obtained directly from clients. Fennelow says that whatever a designer creates from this limited information shouldn’t “be the final solution” and Izatt adds that “the client ends up buying an aesthetic solution as opposed to something that is strategically aligned to their business”. In Roberts’ experience, she often gets the job and later feels she has to “start from scratch” once she knows the client and the project more.

“Sucking time and money out of the sector”

Tenders led by procurement agencies have become commonplace in design and opportunities found on tender portals are often posted by procurement agents rather than the client organisation directly. Procurement agents are employed to help businesses procure the best possible products and services although, according to Izatt, this might not be the case when it comes to design.

He puts the most recent influx of creative pitches down to an increase in “procurement-led processes”. Although a project might appear to have an “exciting brief” on the surface, procurement-led processes mean there is no way of knowing how many agencies are pitching and “who [designers] are actually dealing with” on the client side, says Izatt.

With these processes, there are also “massive amounts of questions about policies and procedures”, rather than what experience agencies have and their way of working, he adds. Even when pitching opportunities do come directly from clients, Izatt says there are not enough people on the business side “who understand how to get the best from an agency”. In his view, clients needs to understand that “design work doesn’t start with a drawing, its starts with an understanding of what they want to achieve”.

Lack of understanding on the client side can also lead to huge pitch calls that include sometimes hundreds of studios. A recent extreme example is a government project that Izatt pitched for, alongside 1300 other agencies.

Applying agencies were not paid for preparing the tender, which invovled a “lengthy portal driven process”, says Izatt, who estimates it cost “at least £1,000 of studio time to complete”. The budget for this project was only £100K, according to Izatt, meaning that this project alone took at least £1.3 million out of the creative sector and put just £100K back in by way of fee payments.

Fennelow suspects that clients who do this think they’re being “diligent” but he feels the practice is “sucking time and money out of the sector”. Ideally, he says a client should start with a higher number of studios on the shortlist and then whittle it down to four or five, as any more would be like “shooting fish in a barrel” and shows that clients “haven’t done their research”.

Roberts, who has recently worked across many exhibition projects, speculates that cultural organisations could be taking advantage of designers wanting to work with them. While she believes a lot of museums use the excuse of being “partly publicly funded” as a reason for doing huge creative pitches, Roberts believes they sometimes do it “because they know they can”.

Like Izatt, she thinks that a lack of confidence in imagining an outcome could also be an issue on the client side. She adds that people outside the creative industries have “an odd idea of what design is”, resulting in designers being treated differently to tradesperson, for example. “A plumber doesn’t have to demonstrate they can put a tap on before you hire them,” says Roberts.

Recommended: Design studios win more business by going against pitching requirements

A two-way street

While Fennelow agrees that creative pitching exists because “clients don’t know how to buy creativity”, he also considers that design agencies “don’t know how to articulate what they do and the value they can bring” without physically showing a client. He notes that some people on the creative side “enjoy the process” of creative pitching, as it allows them to “exercise their creativity” despite “the time and money they’re wasting”.

Studios might take on creative pitches during “a quiet period” or if they’re new to the industry and keen to win work, or simplify fear of missing out on opportunities, Fennelow speculates.

Budget and hours available also affect whether an agency does, or doesn’t, take on creative pitches. “The sector is full of agencies that don’t compare like for like”, says Izatt, adding that creative pitches are less of a problem for bigger agencies that have pitching departments.

Roberts suggests that one way to tackle these disparities would be to have a trade union or membership body, which currently doesn’t exist in the design industry. “If we all agreed to stop creative pitching, then it would stop,” she says.

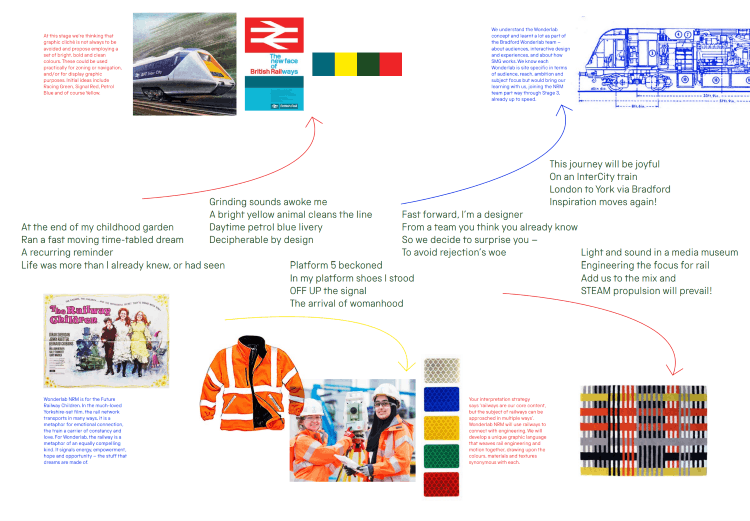

In a recent project where she was asked to creative pitch, Roberts found a loophole. Due to a personal interest in trains, she really wanted to work on the graphics for National Railway Museum’s Wonderlab: The Bramall Gallery and so she pitched, with a four-page poem about trains.

“They wanted a creative pitch and I thought, well, a poem is creative,” says Roberts, adding that the poem was “crafted quite carefully” and included supporting images. She felt it was a “much more enjoyable process” than regular pitches and the poem even referenced her frustration around creative pitching.

Recommended: Sector specialisms: are the risks worth the rewards?

“Talk in the language of business”

So, if creative pitching is the wrong way, what is the right way? The DBA advises agencies to only take part in credentials pitches which allow them to “measure the effectiveness of design” and “talk in the language of business”. Credentials pitches often comprise a detailed overview of the studio, what it does and its process, fees and how it works, along with relevant case studies and client testimonials.

Although taking credentials pitches might take more time on the client’s side, Fennelow says if they reduce the number of competing agencies down according to specialism, size and cost through a pre-decided scoring system, it makes the whole process easier.

Agencies must still be cautious of “a credentials pitch becoming a free pitch with bits of strategy and mock-ups”, says Fennelow. Izatt offers an example where a client was not transparent about the process. He explains how the client had started by asking a larger number of studios for credentials pitchesthen chose a final three and asked for creative pitches.

For Roberts, “the dream” is that a client approaches them directly and asks them to pitch design concepts. To achieve this, Fennelow suggests “positioning your business and illustrating expertise to your target audience” every day in order to attract clients.

While design businesses help clients differentiate themselves from competitors, Fennelow believes that most design studios aren’t as good at doing this for themselves. He thinks “agencies that are better positioned in their field or more specialist” will be asked to pitch less, while pitching might be more of a problem for “agencies that do everything for all types of clients”.

Izatt disagrees, as Thinkfarm is “absolutely sector-agnostic and never wants to specialise. “We look at a sector and the client brief as an opportunity to do something different in that sector,” he says, adding that the studio does this using knowledge gained from working in other sectors.

Banner and featured image credit: Jacob Lund on Shutterstock

- Design disciplines in this article

- Industries in this article

2 responses to “Should designers still be creative pitching?”

Like other professionals, we deserve to be valued for our skills and expertise. We graphic designers should NEVER undertake free pitches. It undermines our worth and the value of our work. Creative problem-solving requires time and effort. We invest countless hours developing unique concepts for our client’s needs. By accepting free pitches, designers essentially give away their time and talent, diminishing the value of their expertise. Free pitches also devalue the worth of our entire design industry. It perpetuates the notion that creative work is not worthy of compensation. In my whole professional life, I have not taken on an unpaid pitch. I have done pro bono jobs for charities I wanted to support or in helping a friend, but that’s it. I will call them out when I can show evidence of a potential client asking me to free pitch. DW may recall several years back; I shared emails that I’d had from a museum asking me to submit a free creative pitch. Ironically, I later learned that an exceptionally well-known design consultancy did a free pitch on that project. When designers accept such requests, it sets a precedent for future clients to expect free work. Ultimately, it diminishes the professional standards of our industry, making it harder for designers to negotiate fair compensation in the future. My advice is DON’T DO IT.

Never free pitches!!!!!!!!